Free Will and Divine Providence

One of the big questions relating to reincarnation is how can the soul have free will if it is a reincarnated soul that brings with it very set effects from a previous lifetime? Doesn’t the accumulated weight of the reasons the soul is reincarnated and the very specific rectifications it is called upon to do infringe on the soul exercising any measure of autonomy and true choice? To understand the answer to this very important and real question we must first discuss free will and Divine Providence in general, and then apply what we learn to this specific question.

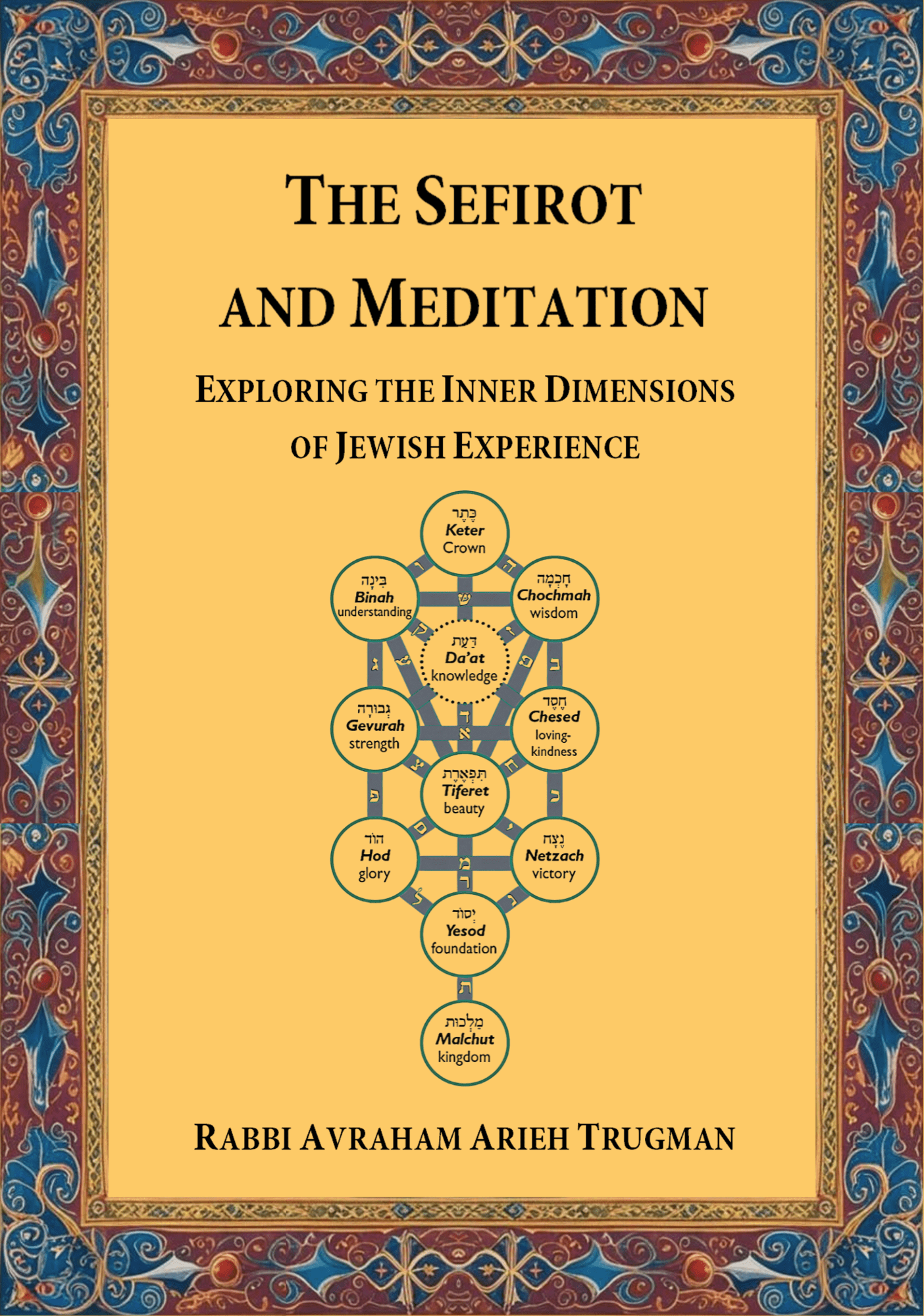

When probing deeply into the nature of the world one finds paradoxes everywhere, from the spiritual realm to the modern description of reality according to relativity and quantum mechanics. God Himself is referred to in Kabbalah as “[the one] who carries opposites” (Likkutei Torah 3:68) or as “Paradox of Paradoxes” ( Teshuvat HaRashbah 18). God is described similarly in a number of parables that express the mystery of Divinity and the creation such as “He is the place of the world but the world is not His place” (Genesis Rabba 68:9) and “[He is] present yet not present” (Sefer HaMama’arim 5679; pp.237 ff).

Rabbi Akiva said: “Everything is foreseen, yet the freedom of choice is given. The world is judged in goodness and everything depends on the abundance of good deeds” (Pirkei Avot 3:19). According to many commentators the greatest paradox in relation to man is that both free will and Divine Providence operate simultaneously. Most religions or philosophies tend to lean very heavily to one of these possibilities at the expense of the other, or totally negate one or the other, while Torah embraces not only this paradox, but in fact all paradoxes, as reflecting a deeper and truer reflection of reality. That both free will and Divine Providence can both be true stretches the mind to comprehend that which is just beyond grasp. Yet the stretching the mind is of great value and gives us deeper and deeper insight into how life unfolds.

Despite Judaism’s firm belief in free will it is not an absolute independent of other factors. Maimonides, one of the strongest proponents of free will, states clearly that if one’s sins become very great the gift of free will is taken away (Mishnah Torah; Hilchot Teshuva 6:3). Free will is not open ended – if one abuses his freedom of choice enough he in effect loses the privilege of using it.

It must also be stated that many times we think we are exercising our free will but in truth we are no more than reacting to a plethora of biological, psychological, emotional and behaviorist factors. The true exercise of free will is a very precious commodity and in fact not as common as supposed. Giving into our animal natures, following the crowd and being overly influenced by society all limit the true exercise of free will.

There has been a famous debate in the social sciences regarding which factors influence a person more in determining their path in life, and subconsciously, many of their decisions – nature or nurture. Do genetics rule or does one’s upbringing over ride a person’s more instinctual and inherited temperament? Yet when reflecting on this debate we see that in relation to true free will, both nature and nurture are on one side, while the ability to rise above all influencing factors and to make decisions from a real objective outlook is on the other side.

The point is that although we firmly believe in free will we need to have a more real and objective understanding of what we are talking about. This is very important regarding our original question, for as we discussed above, we are born against our will, die against our will and are judged against our will. In other words, free choice operates within specifically defined and somewhat limited parameters. And there is no way of avoiding the many influences already mentioned above – they are a fact of life.

In a fascinating teaching the Talmud records the following pre-birth scenario: “The angel appointed over pregnancies takes a drop to the Holy One and asks Him: Master of the universe, what will become of this drop? Will it be strong or weak, wise or foolish, wealthy or poor? The angel doesn’t ask: Will it be wicked or righteous? This is in accord with the statement of Rabbi Chanina: All is in the hands of heaven except the fear of heaven” (Niddah 16b).

The implication of the above teaching is that a person being strong or weak, wise or foolish, rich or poor, and in fact many other factors in life are determined to a great extent before birth. These things depend, and are realized, through a combination of genes and the specific circumstances that one is born into. What though determines these factors? From a spiritual point of view they come from the specific circumstances deemed necessary for each soul to fulfill its particular purpose and rectification. And according to the teachings of reincarnation, these specific factors are determined in large measure from previous lifetimes.

The predetermined circumstances into which a person is born are referred to as mazal, as in the Talmudic statement: “Life, children and sustenance do not depend on merit, rather on mazal” (Moed Katan 28a). The constellations are called mazalot, and infer predetermination, due to many ancient people’s firm belief in the ruling power of the stars. Mazal also means “flowing.” One’s mazal are those things that flow to a person from Above and are predetermined for a person’s ability to accomplish what they need to in life, but here too, as in the description of free will, it is not so black and white. A person may be given every blessing and opportunity to succeed both physically and spiritually, but through his or her own lack of maturity or refinement fail miserably. Or the opposite – one may be born with every strike against him yet succeed beyond all expectations. This is the power of free will. What we are given is predetermined, but what we do with what we are given is in our hands. Yet this is not so simple either as we will now see.

Although each person has their own particular purpose in life, there is a much bigger picture we all fit into. Just as an individual is bound by many predetermined factors and circumstances, so too are the Jewish people and in fact all mankind. Ever since the sin of Adam and Eve we are all bound by the results of the primordial exile from the Garden of Eden and the accompanying “curses.” This creates the existential reality in which we live and die, the parameters over which we have no choice.

The Jewish people in particular are bound to a covenant with God and all that it entails. When God made the first covenant with Abraham at the “covenant of the pieces” he was told that his progeny would be afflicted by another nation in a land not their own for four hundred years but after words they would come out with great wealth (Genesis 15: 1-21). This prophesy became manifest in the slavery in Egypt and their ultimate redemption. The question becomes: what choices did they have during those four hundred years as to their fate? Was it not predetermined?

The answer is both yes and no. On a certain level history unfolded as it was determined to, yet the actual way and each person’s role in that unfolding was highly fluid. This holds true in general for how Divine Providence and free will operate simultaneously. Joseph when he finally revealed himself to his brothers who had sold him twenty-two years before said: “Therefore do not be sad nor angry with yourselves that you sold me here, for God sent me here before you in order to preserve life” (Genesis 45:5). Later Joseph said to them: “But as for you, you thought to do me evil, while God meant it for the good…” (Genesis 50:20). Free will once again is shown to be somewhat relative. The brothers made their choices and acted accordingly, yet Joseph reveals to them that in affect they were fulfilling a higher imperative unknown to them at the time. The mystifying manner in which individual choices and Divine Providence dovetail regardless of the choices made lies at the heart of the paradox. God is infinitely adaptable and no matter what choices a person makes God makes sure the individual’s ultimate purpose is fulfilled. This holds true for all mankind as well. When needed, God intervenes in open or hidden ways so that a person stays somewhat on the right path. Whether it takes an individual one life time or a hundred is all adaptable in an accounting only God knows. The same holds true for how long will it take till the world to be ready for the Messianic era and the fulfillment of man’s ultimate purpose.

Yet in this matter as well there is a merger of free will and Divine Providence. In the book of Isaiah when speaking about the final redemption God says through the prophet: “In its time I will hasten it” (60:22). The Talmud asks: If it is in its time, meaning a set determined time, how can it be hastened? The Talmud answers: If they merit it will be hastened, if not it will be in its appointed time (Sanhedrin 98a). Yet, the Talmud also predicts that this cycle of history and life on earth as we know it will last six thousand years, followed by the Messianic era (Sanhedrin 97a). Once again the line between free choice and Divine Providence become blurred.

Earlier we brought the Rashi who explained that the “fallen one” is destined to fall off the roof; just be careful that it not be your roof. History unfolds according to a dynamic set to fulfill God’s ultimate plan for all mankind. Each person in every generation plays his or her part. Every individual affects the whole, and the whole affects the individual. The very important principle – “All of Israel is responsible one for the other” – is learned from the verse in Leviticus (26:37) that “they shall fall one man upon another.” The Talmud explains that one man will stumble by the sin of another, thus teaching us how every Jew is responsible one for the other (Shevuot 39a).

The Jewish people are told repeatedly by Moses that the covenant with God entails clear rewards and punishments and unambiguous laws of cause and effect. In a classic formula of free will he puts the choice before them: “I call heaven and earth today as witness this day against you, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse – therefore choose life that you and your children shall live…” (Deuteronomy 30:19). Despite this, Moses tells the people shortly afterwards that they will in the end rebel against God and the Torah lays out exactly how Jewish history would unfold. Anyone knowing even the basics of Jewish history can see that everything the Torah predicts has come true. This brings us back to our question as how does individual free will operate within the strictures of a people’s predetermined history.

Perhaps the greatest advice as how to balance these two realities is given in Pirkei Avot (2:4): “Make His will your will, so that He will make your will His will. Nullify your will before His will so that He will nullify the will of others before your will.” According to this wisdom our ultimate goal is that our free choice should exactly reflect His Providence.

We now take our discussion regarding free will and Divine Providence and apply it to our original question regarding reincarnation – how can we have free will if our present existence is determined by the effects of previous life times.

The effects of previous reincarnations as we have seen are actually just one among a host of dynamics affecting a human being. Reincarnation then is but one of the many factors influencing a person and just like one can either overcome or succumb to certain forces and drives in life, so too, through free will one can surmount the effects of previous lifetimes, or alternatively, be stifled by the ghosts of the past.

According to the Talmud discussed above many circumstances of a person’s life are decided before their birth. All of these decisions are part of the Divine judgment that certainly takes into consideration what a person did or did not do in a previous lifetime. Yet, even a soul that is sent below into a body for the first time only does so with a very specific individual purpose, which is in addition intrinsically connected to the overall plan of creation. In this sense, our freedom of choice has very defined parameters and is not as absolute as we might think.

A general principle of reincarnation as taught from a Jewish perspective states that despite the fact that previous lifetimes most certainly help shape the circumstances of a persons life, each new lifetime is not burdened by the negative energy of a previous lifetime. In other words, the challenges and the rectifications that are needed to fix prior mistakes present themselves in each new lifetime, but the choice to actually deal with these remains ours. Even if for example the results of a previous lifetime cause us to be born poor, weak or handicapped in some way, a person still has the freedom to choose how to relate to that situation and with what attitude he or she will approach life. It is in fact only through the granting of free choice that we could come to rectify the effects of our past. For without free will we would inevitably fall into the same mistakes as previously.

Therefore, although reincarnation does most certainly affect our lives, the negative traits, actions or attitudes do not carry over in the sense of binding us to these old patterns of behavior from one life to another. This is an important general principle: negativity in its essence does not transfer from lifetime to lifetime, whereas the essence of good is transmitted between lifetimes. This is a result of God’s chesed, His loving kindness, which is reflected in the word gilgul numerically equaling chesed. Yet even the good of a previous lifetime does not guarantee the soul will translate it into a true rectification of the past. This still lies in the realm of free choice that each person is granted, no matter what their past.

Each life is considered a new beginning, a clean slate, and is judged wholly on its actions in this lifetime. In fact it is considered easier to repair mistakes from a previous lifetime, since now with a certain distance from the intellectual and emotional confusion and turmoil that caused the original blemishes, the soul is in a more objective and conducive environment to fix that which is in need of repair.

Judaism emphasizes the uniqueness, purpose and importance of each individual and the critical role of free choice in shaping ones destiny. The whole point of reincarnation is not to be bound by the past but to elevate oneself beyond all obstacles here in the present. Even though a soul may return many times to this world it is never exactly the same soul and it is certainly not the same body. Therefore despite an obvious connection from lifetime to lifetime it is a totally new combination of soul and body dynamics at play.

Just as free will operates in some mysterious way simultaneously with Divine Providence, similarly an individual soul with free will operates in the strictures of reincarnation and many other forces of the past shaping its present reality. Along with our individual fate and destiny we are all connected in one way or another to God’s plan for creation as a whole. This is especially pertinent to the Jewish people who are bound to God by an everlasting covenant and a specific mission in the world, as will be discussed further in chapter five.

A fascinating insight into the connection between Divine Providence and gilgul is found in a letter Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, wrote to an individual in 1949. In the letter he addresses the Baal Shem Tov’s concept of Divine Providence. Before the Baal Shem Tov there were many questions whether God’s Providence was of a more general or a more specific sort, and to what extent and to whom did it extend. The Baal Shem Tov taught that God’s Providence is specific and particular and all inclusive, extending over mineral, vegetable, animal and human, from an individual atom to the largest galaxy.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe then raised the well known question whether God’s Providence is over all creation because according to the teachings of reincarnation (as we will see in chapter four) every strata of creation contains human souls, or at least in potential could contain human souls, and therefore God’s Providence extends to all creation on the merit of these souls manifest in gilgul. This was the position stated in the Kabbalistic book Chesed L’Avraham. Rabbi Schneersohn maintained that while the Baal Shem Tov believed that souls could return for a specific time in all different levels of creation, but that this was certainly not true of every point of creation. The Baal Shem Tov’s position was that God’s Providence extended to every particular point of time and space on its own merit independent of the teachings of gilgul.