Judah, King David, and Repentance

The Talmudic dictum that “the actions of the fathers are a sign to the children” (Sotah 34a) plays a central role in the Torah and in our own lives. In Vayeishev, Judah’s words and actions pave the way for his descendants to engage in teshuvah, sincere repentance, one of Judaism’s cornerstones. No portion could be more appropriate for this theme than Vayeishev, as the words “teshuvah” and “vayeishev” both have a common two-letter root, shev, which means “to return.”

After selling Joseph into slavery on Judah’s advice, his brothers realized their error and blamed Judah for not having stood up to them and foiled such a plan. Judah was so upset at the turn of events and his part in selling his brother that he went into voluntary exile: “And it came to pass at that time that Judah went down from his brothers” (Genesis 38:1).

During this period, Judah married and had three sons. His first son married Tamar but died because rather than impregnating Tamar, he spilled his seed. She then married Judah’s second son in a levirate marriage, but he too died as punishment for the same misdeed. Judah then promised her his third and last son, but he did not fulfill his promise

Tamar, a righteous and holy woman, was driven by a prophetic sense that she was destined to have children from the family of Judah and that their descendants would be kings and redeemers. In order to ensure that this would happen, she disguised herself as a harlot and enticed Judah, her father-in-law, into unknowingly sleeping with her. When she became pregnant, Judah condemned her to death for sleeping with another man and not waiting for his promised third son. She sent Judah proof only he would understand that she had slept with him. Judah now had a choice: he could either admit his deed and free her or let her go to her death. He takes the high road, publicly proclaiming that “she is more righteous than I” (Genesis 38:26) and expresses remorse that he had not given her his third son in marriage. The Torah then recounts that “he did not know her [intimately] further” (Genesis 38:27).

Rambam, in his classic Mishneh Torah (in the section entitled Hilchot Teshuvah [The Laws of Repentance 1]) lists three prerequisites for true repentance: confession, remorse, and a commitment not to repeat the same action in the future. Judah undertakes all three steps, and his repentance becomes the model for all Jewish repentance – “the actions of the fathers are [indeed] a sign to the children.”

One of Judah’s direct lineal descendants, King David, bears out this dictum. After King David secretly has relations with Bathsheba he tries to cover up his behavior by sending her husband to the frontlines where he is killed. The prophet Nathan visits David and tells him the tale of a rich man who oppresses a poor man by taking his only sheep from him. David is outraged and exclaims that the rich man should be severely punished. The prophet reveals to King David that the tale was actually a parable: King David is the guilty rich man. King David also undertakes the three crucial steps to repentance. Without hesitation, he immediately declares, “I have sinned” (2 Samuel 12:13). He spends the rest of his life in a constant state of repentance, as any reader of Psalms can attest, and, of course, he never does such a thing again.

It is interesting to note that in Hebrew Judah’s confession consists of two words, while David, who was a direct descendant of Judah and Tamar, confessed with just one word. Judah’s confession clearly had a great influence on David, either consciously or subconsciously. As the first time in the Torah that anyone admitted a mistake and confessed, Judah’s confession truly becomes an archetypal case of “the actions of the fathers are a sign to the children.”

Significantly, while the Torah refers to the Jewish people as Hebrews or the children of Israel, we are now commonly known as Jews. This appellation in Hebrew comes from the name Judah, for he not only paved the path to teshuvah for himself and his descendants, but was also the progenitor of the Davidic monarchy, the legendary ruling house of the nation of Israel. While technically speaking, the Jewish people were called Jews because Judah’s descendants made up the bulk of the Jewish nation after the 7th century BCE (when ten of the twelve tribes were exiled by the Assyrians), this historical fact does not seem to be an accident of history. Judah had a profound impact as a leader and progenitor of the Jewish nation. Similarly, King David had a profound impact, for he not only achieved teshuvah for himself, praising God all the while, but also taught all subsequent generations how to do this.

Even though the Sages explain that technically David was not guilty of either adultery or murder, his exact sin is still open to some debate. David certainly felt he had done something wrong and spent his entire life repenting for it. In an attempt to explain how David could have done what he did, the Sages explain that these actions were so not in character that on some level these events only came to pass “in order to teach the individual how to do teshuvah” (Avodah Zarah 4b). Many commentaries explain that in some mysterious way God “arranged” the entire incident, not only to provide David with a test that could lead to his spiritual advancement but, should he fail, to provide a model for the Jewish people of how to repent and return to God’s good graces.

The idea that God “orchestrates” such predicaments is echoed in Judah’s earlier confession: “She is more righteous than I.” Rashi explains that the sentence can be split in two and read as “She is more righteous – from me,” the latter part intimating that Judah was responsible for impregnating her (“she is pregnant from me”). Rashi continues with the words of the Sages who explain that first Judah declared “she is more righteous” to attest to the truth of her words, and then a voice from heaven separately declared: “[It is] from Me [God, that this whole affair came about so that from their union future kings in Israel would descend.]”

Another Midrash, echoing the same notion that God orchestrates events, explains that when the Torah uses the phrase, “It came to pass at that time” (Genesis 38:1), it is alluding to a number of simultaneous events: At the time that the brothers were busy selling Joseph; Joseph, Jacob, and Reuben were all in mourning – wearing sackcloth and fasting – because of the events surrounding Joseph’s sale; Judah was occupied in finding a wife; and God, at the very same time, was busy preparing the light of the Mashiach (Bereishit Rabbah 85:1). In other words, the brothers’ heinous actions and Joseph, Jacob, Reuben, and Judah’s reactions were all enigmatically “orchestrated” by God who was setting the wheels in motion for the coming of the Mashiach.

Returning to the issue of confession, the root of the word to confess (lehodot) means both to praise and to thank. All three meanings were united in David, “the sweet singer of Israel” and the composer of the Psalms. In these eternal expressions of the full gamut of human emotions, David continually weaves together his gratitude and praise for the Creator and his deep faith in His nearness. Both Judah and David clung to God even when everything seemed to be going wrong, even when they felt all alone. This too was a path they paved for their descendants.

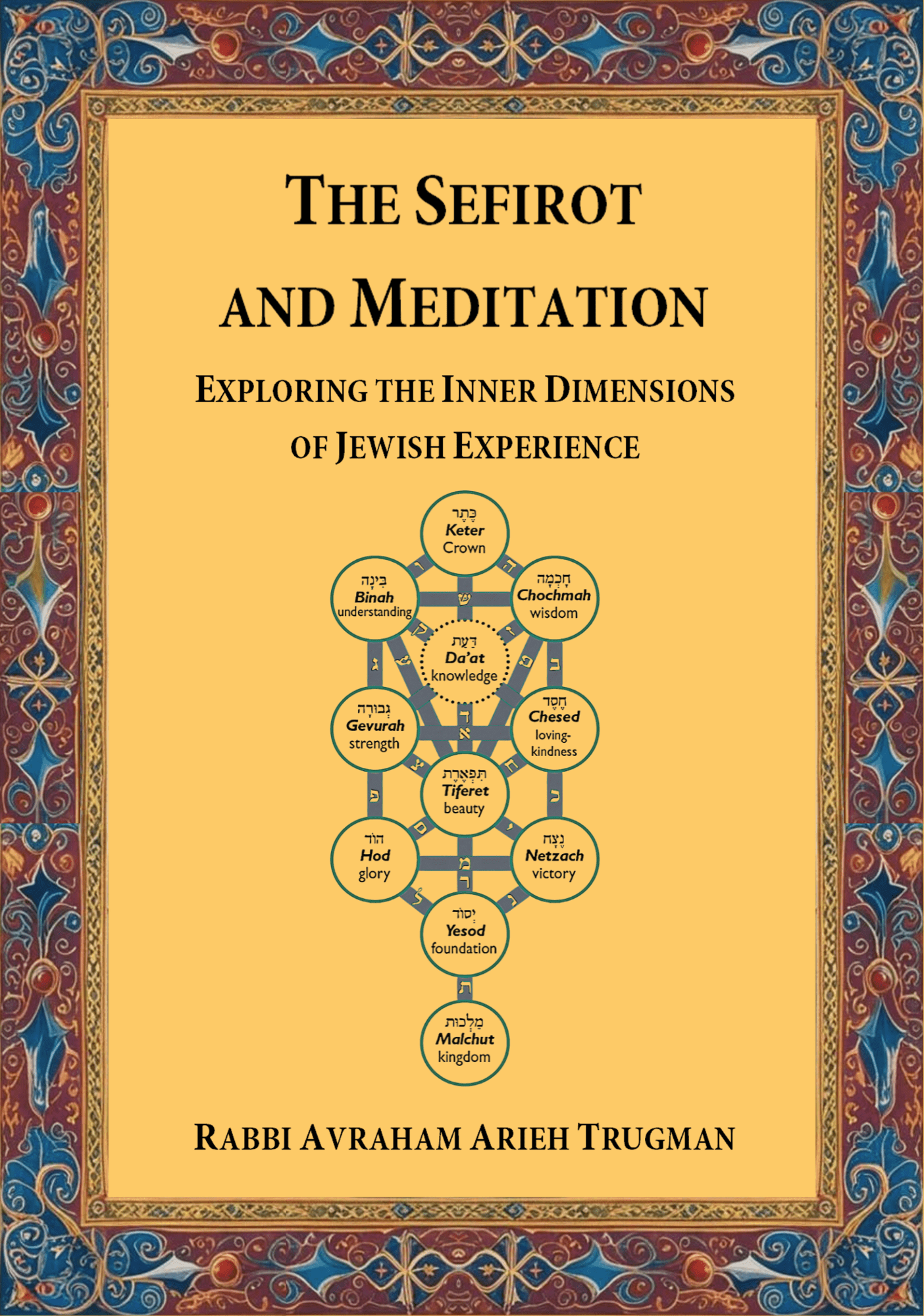

The name Judah in Hebrew consists of the four letters of God’s name and the additional letter dalet. It is as if David’s soul, whose name begins and ends with the letter dalet, is enwedged into the soul of Judah, who paves the path to teshuvah for him and all future generations. The middle letter of David’s name is a vav – a vertical line meaning “and” – which both graphically and semantically represents the notion of connection and the soul’s eternal bond to its Creator.

In addition to containing the four letters of God’s essential name, the name Judah significantly comes from the root hod, which means confession, praise, thanksgiving, and glory. More than anyone else in Jewish history King David embodied all these meanings of hod. The letter dalet, as a rule, represents great humility and self-nullification. Paradoxically, David’s deep inner sense of lowliness enabled him to express God’s glory through his own kingship.

The Mashiach will descend from Judah and David’s royal house. He will teach the whole world the true meaning of teshuvah, showing the world’s entire population how to completely return to God. This sincere teshuvah will be accompanied by genuine songs of praise, exalting God and filling the human heart with love for the Creator.