Everywhere we look we see cycles in our lives; cycles of time, the subtle changes of the colors of the sky as the sun makes its daily orbit across the heavens, the moon as it waxes and wanes, seasons changing, the ebb and flow of the tides, life cycle events, the daily emotional roller coaster we ride, while history seemingly repeats itself endlessly. Birthdays and anniversaries mark significant days year after year. Holidays repeatedly march across the calendar with their historical remembrances and their deep connection to nature and the seasons.

The cycle of life and death, dormancy and rebirth is engraved in every strata of reality – from the personal to the universal, from the practical to the mystical. Seeds that disintegrate in the ground release their germ of life that sprout and grow, giving forth fruit and their own seed, eventually succumbing to the inevitable cycle of disintegration from where it began. Sparks of fire when fanned become roaring flames, only to turn into coals and ash. And of man the Torah states: “By the sweat of your brow shall you eat bread until you return to the ground from which you were taken: for you are dust and to dust shall you return” (Genesis 3:19).

King Solomon in the Book of Ecclesiastes dwells on this theme extensively when contemplating the existential reality of man:

“A generation goes and a generation comes, but the earth endures forever. And the sun rises and the sun sets – then to its place it rushes; there it rises again. It goes towards the south and veers towards the north; the wind goes round and round, and on its rounds the winds return. All the rivers flow into the sea, yet the sea is not full; to the place where the rivers flow, there they flow once more” (Ecclesiastes 1:4-7). King Solomon continues and develops this idea in the third chapter of Ecclesiastes (3:1-8) in the most beautiful and poetic manner:

“Everything has its season, and there is a time for everything under the heaven:

A time to be born and a time to die;

a time to plant and a time to uproot the planted.

A time to kill and a time to heal;

a time to wreck and a time to build.

A time to weep and a time to laugh;

a time to wail and a time to dance.

A time to scatter stones and a time to gather stones;

a time to embrace and a time to shun embraces.

A time to seek and a time to lose;

a time to keep and a time to discard.

A time to rend and a time to mend;

a time to be silent and a time to speak;

A time to love and a time to hate;

a time of war and a time of peace.”

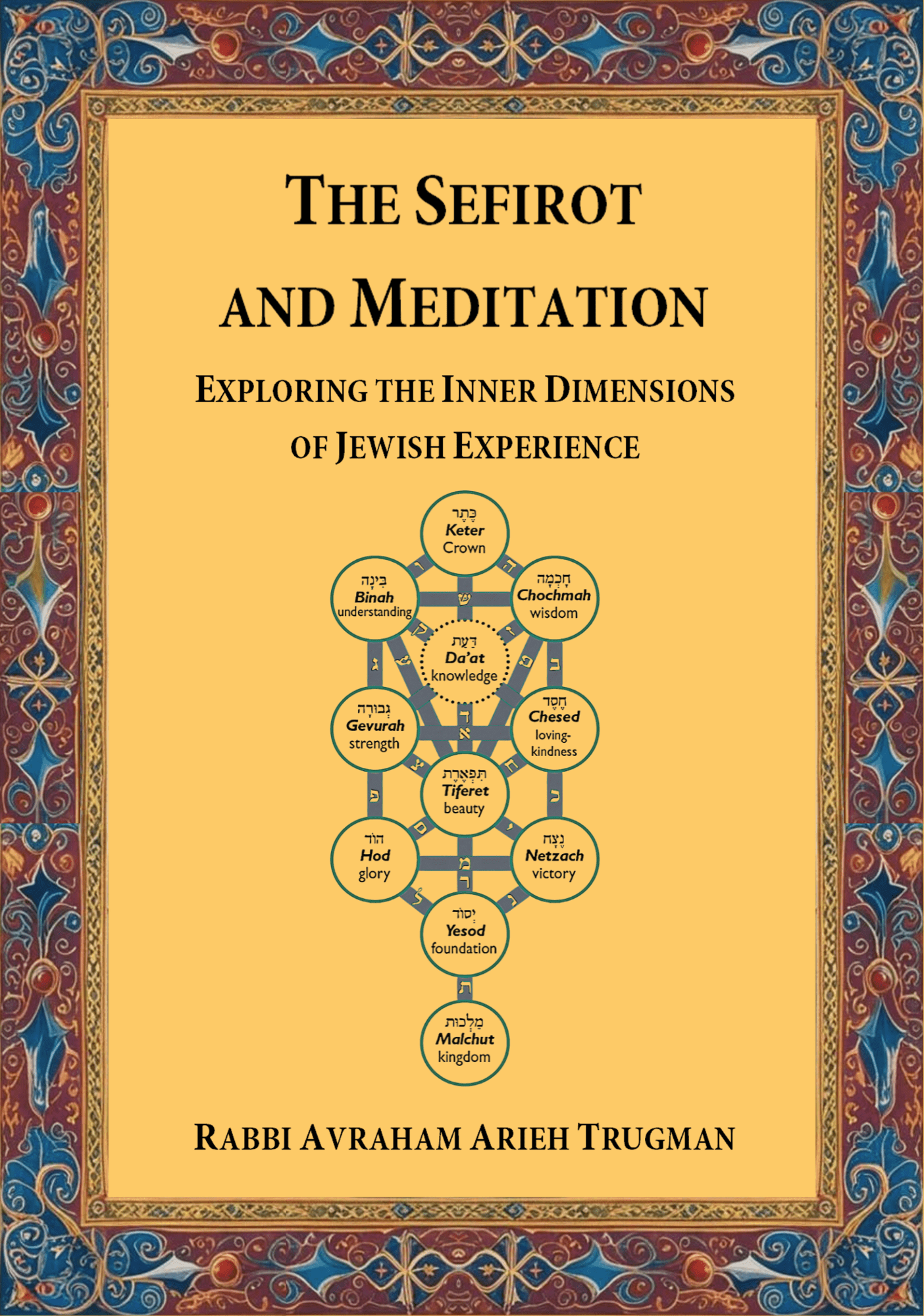

An important teaching of the Sages states that “God looked into the Torah and created the world” (Zohar 1.134a). The Torah thus serves as the blueprint of reality. This teaching of course goes against man’s more natural logic which would express it as just the opposite – the Torah is a reflection of the world we live in. I heard a similar idea expressed once by Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, who said that we may think we were redeemed from the slavery in Egypt in the spring, to correspond to the time when nature is renewing itself and coming to life, but, he said, its actually just the opposite – spring comes back to life and is rejuvenated because the Jewish people came out of Egypt! Now at first glance this statement flies in the face of normative logic – the cycles of the seasons certainly preceded the exodus from Egypt – not the opposite. For many years I could not grasp what he meant until the following understanding dawned on me.

As the Jews are leaving Egypt the Torah states: “It was at the end of four hundred and thirty years, and it was on that very day that all the legions of God left the land of Egypt. It is a night of anticipation for God to take them out of the land of Egypt, this was the night for God: a protection for the Children of Israel for their generations” (Exodus 12:41-42). Rashi explains “on that very day” to mean that on the 15th of Nisan [the day of Pesach and the exodus from Egypt] the angels came to Abraham to announce that he would have a child [with Sarah], on the 15th of Nisan, Isaac was born and on the 15th of Nisan God first revealed to Abraham at the “Covenant of the Pieces” (Genesis 15:1-20) that his descendents would be slaves for four hundred years. On the words “a night of anticipation for God” Rashi comments that God had guarded and anticipated this day – the 15th of Nisan – as the day to fulfill His promise to take the Jews from Egypt.

From these verses and the commentary of Rashi we understand that there was something intrinsically special about this date; that the drama of the exile and redemption from Egypt were purposefully “locked” into this particular day. Thus the terms “on that very day” and “ a night of anticipation for God” represent a certain potential energy within this specific day, waiting to be activated and fulfilled. This teaches us that in a sense, days don’t become holidays, holy and special, only because certain events happen on them, but that events happen on certain dates because they have within them a supernal energy waiting to be revealed in the events of man.

In the song of HaAzinu from the book of Deuteronomy it states: “When the Most High divided to the nations their inheritance; when He separated the sons Adam, He set the bounds of the people according to the number of the children of Israel” (Deuteronomy 32:8). Yet, the seventy archetypal nations appear chronologically before the seventy souls of Jacob/Israel! From this we understand that the archetypal model of the seventy souls of Jacob in a spiritual sense preceded the seventy nations. The archetypal nations are seventy because the souls of Jacob would be seventy. It is taught in the Midrash: When the thought first arose in the “mind” of God to create the world, the thought of Israel arose first (Breishit Rabbah 1:4; Tikunei Zohar 6). Just as God looked into the Torah and created the world, He first thought of Israel, the archetypal ideal man, and created the world to correspond to His initial thought and ultimate purpose.

On the first letter of the first word of the Torah, breishit, “in the beginning,” Rashi explains that the letter beit, means not “in the beginning” but “for the sake of the Torah that is called ‘beginning’ and for the sake of Israel which is called ‘beginning’ – for that reason God created the world.

Another intriguing Midrash states that when God was creating the seas He created them on condition that when the people of Israel would come to the Reed Sea, pursued by the advancing Egyptian army, that it would split for them. When taking the above teachings in our tradition (and many more) describing the purpose of creation for the sake of man in general, and Israel in particular, and applying them to the concept of cycles, an amazing idea is revealed. It is not so much that we were created in order to be in tune with nature and the cycles all around us, as much as the cycles of nature and the specific cycles of time as revealed in the Torah were created with us in mind. In other words, the reality of cycles is ingrained and encoded in all levels of physical creation because these cycles are necessary for man to reach his true potential as an “image of God.”

At all times two seemingly opposite perspectives confront man. On one hand man is but a speck in the overwhelmingly vast universe of billions of galaxies. Of this reality Abraham exclaimed: “I am but dust and ash,” (Genesis 18:27) and David proclaimed: “When I behold Your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars that You have set in place [I think] ‘What is frail man that You should remember him and the son of mortal man that You should be mindful of him.’” David in the next verse answers his own question: “Yet, you have made him but slightly lower than the angels and crowned him with soul and splendor. You give him dominion over Your handiwork, You place everything under his feet…” (Psalms 8:4-7). Our Sages teach us that each person should see the world as if it was created just for them (Sanhedrin 37a; in the Mishnah). Science in a manner confirms this world view by showing how seemingly implausible it is for life to be maintained on planet earth and how even slight changes in a host of physical phenomenon and factors would make life utterly impossible. It appears that life and man’s presence were carefully crafted in the conditions on earth.

Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh teaches that although we know the earth revolves around the sun, the fact that God made it appear to us that the sun revolves around the earth is just as important. These two seemingly opposite truths symbolize the existential paradox of man and the constant challenge of confronting apparent duality, while perceiving the oneness and unity behind them. Einstein grappled with this from a scientific perspective and proposed the unified field theory, by which all forces in the universe are in essence one. Science has gone on to accept this idea and the quest is now to find the proper scientific formula or equation that will not so much prove it, but to open the possibility of harnessing that unity.

By studying the various cycles of time, the laws of nature and the cycles inherent in Jewish life, we come into contact with the primordial energy of creation put into place for the sake of man. We can now understand that from a certain perspective the Jewish people did not come out of Egypt to correspond to the spring, but spring contains the energy of rejuvenation and renewal because it fits the needs of man and the Jewish people, who were destined from the beginning of time (and even before) to come out of Egypt.

This brings us to an even deeper understanding of the story of the Jews in Egypt as the prototype of all manifestations of exile and redemption. The Torah is not speaking about only a localized event in history, rather an allegory of all reality. This is true of all the stories in the Torah, each one serving as eternal teachings on a multitude of levels – from the practical to the mystical, from the physical to the spiritual.

The root word for “world” in Hebrew, olam, also means “to hide.” The world paradoxically both reveals and hides God within nature. In the deepest sense the cycles of time and nature are patterned on the needs and inner world of man, which in turn mirrors the Divine Creator. By observing the cycles of time and nature as revealed in the Torah, and through direct experience, we connect to a more spiritual Divine flow and perception of reality.

By understanding the Divine cycle of seven, as manifest first in the six days of creation and the culminating Shabbat, and subsequently sealed in all cycles of Jewish time and ritual, we enter into a Divine context of time. Through aligning ourselves with the Jewish calendar, based on the monthly renewal and cycle of the moon and by flowing with time in the context of the holidays as they correspond to nature and the agricultural cycles of Israel, we open ourselves to the underlying framework and allegory of cycles in our lives. By studying the changes of nature and the seasons, we become privy to fundamental lessons of spiritual and emotional growth.

When we are slaves to time and not in tune with the secrets of cycles, time appears to be linear, a cold and impersonal force constantly moving beyond our control. When we start to understand the mysteries of time and cycles we begin to experience time as more circular, continually renewing and repeating itself. When we become masters of time we come to realize that time is a four dimensional spiral, continuing to return to the same place, but at each revolution on a higher plane. In this way the past, present and future flow through the same vertical coordinate on the spiral, always meeting in the eternal present moment. This secret is alluded to in the verse: “and Abraham was old, he came into days, and God blessed Abraham with everything.” (Genesis 24:1). Came into days represents Abraham mastering time, by which he could experience this world and the world to come – the past, present and future -simultaneously. This is why the first mitzvah, commandment, given to the Jewish people as a nation in preparation for leaving Egypt, was how to mark time and formulate a Jewish calendar (as will be explained in greater depth in chapter four.) Being a master of time is the main ingredient needed for going from slavery to freedom, from finite borders to a state of eternity.

2

In addition to all the various cycles included in the Written Torah, the Sages, well aware of the importance of cycles in Torah, nature, history and the human psyche, crafted a myriad of rituals, laws and customs to accentuate this reality. The daily, Shabbat and holiday prayers are written and arranged to accentuate the rhythm and changes of time, season and appropriate historical context. Many of the prayers are arranged according to the order of the Hebrew alphabet in order to emphasize process and completion. We add prayers for rain and dew in their appointed seasons. On the Shabbat before a new moon we announce it in synagogue and recite prayers that make us aware of the energy of the upcoming month. Before each full moon we sanctify the moon’s cycle and its symbolic meaning for the Jewish people.

We eat an egg, due to its roundness, in a house of mourning to remind us of the cycle of life and death. We eat chickpeas on the Shabbat after the birth of a child to remind us of the same. A bride circles her groom seven times under the chuppa, the wedding canopy, and seven blessings are recited for bride and groom for seven days afterwards. Married couples observe the laws of family purity which follow a woman’s biological rhythm in order to sanctify their intimate sexual relations.

The holiday of Simchat Torah is celebrated by dancing in circles for hours with the Torah, before its final portion is read and then immediately rolled back to the beginning where we start again. The beginning of Shabbat is marked with lighting candles and reciting kiddush, the sanctification of the day on wine, and ends with the ritual of havdalah, when, with a candle and wine, we formally separate the Shabbat from the days of the week. And the list goes on and on….

Implied in the idea of cycles is the concept of renewal and rebirth. In the first mitzvah given to the Jewish people, mentioned above, the root word for “month” which is also the root word of “newness” appears three times in the same verse: “This month shall be for you the beginning of the months, it shall be for you the first of the months of the year.” Exodus 12:1). The concept of renewal is so important it is incorporated in the first mitzvah in order to teach us that it is the emotional and psychological foundation of all spiritual service.

Through a long history of constant persecution and upheaval, the Jewish people have in fact been able to begin again countless times. Through exiles, slavery, crusades, expulsions, crusades, pogroms and holocaust, the Jewish people have managed to renew themselves in ways beyond historical precedent and logic. It is very much at the core of not only Jewish survival, but national and personal achievement of Jews throughout the ages.

Jewish thought has always posited the concept of creation “something from nothing.” Science scoffed at the idea till the Big Bang theory of creation in effect proved it. Each morning in our prayers we praise God who renews daily the works of creation. The creation of the world is not seen as a one time act, but constant creation at every moment. Recently science has discovered within the atom, small sub-atomic particles that constantly are being created, bursting in and out of existence for no matter than a billionth of a second. These mysterious particles which are being created constantly “something from nothing” lie at the very foundation of our world.

Here then is another duality needing careful balance. On one hand the world is being re-created at every moment while simultaneously the rhythms of life and the laws of nature repeat themselves in patterns and cycles. A human being psychologically needs novelty and innovation in order not to be overwhelmed with boredom and dissatisfaction, as well as stability and order so not to be swept away by constant change. Both of these requirements of a sound emotional state need to be addressed and fulfilled. Tradition roots us, giving us meaning, identity and context, while a sense of individuality and newness give us the ability to add our special link to the chain of generations.

Jewish life in all its various richness is constructed to gratify the various psychological, emotional, spiritual and material needs of man. There is a time to work and a time to rest, a time to be joyous and a time to cry, a time to transcend the body and a time to fill its most basic desires, a time to be an individual and a time to stand with a community, a time to give and a time to receive, a time to follow tradition and a time to innovate, a time to plant seeds and a time to lift up the sparks.